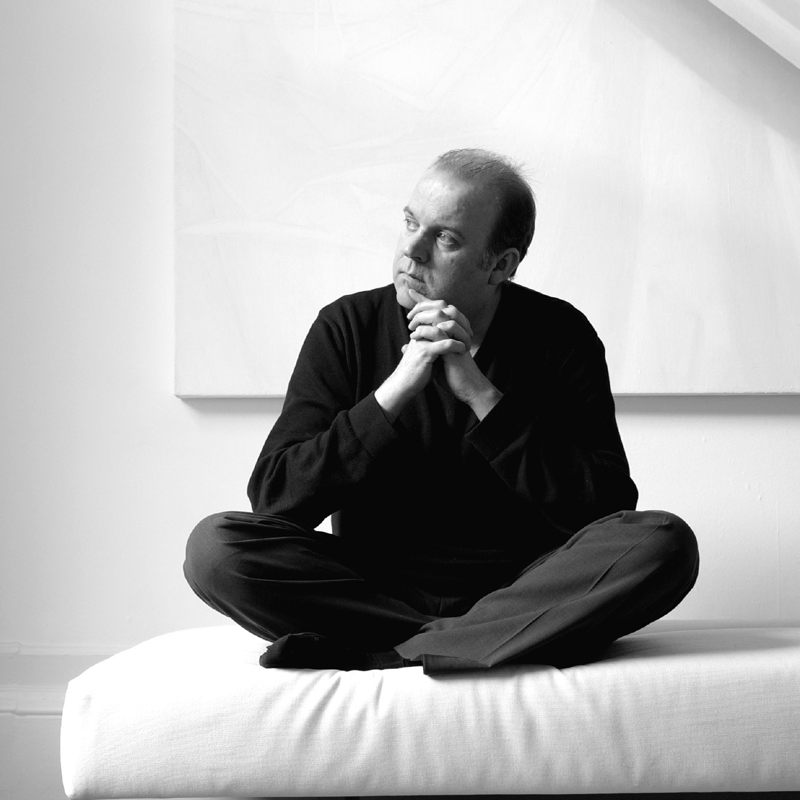

Craig Armstrong

23 pieces at nkodankoda sheet music library

over 100k editions from $14.99/month

Hassle-free. Cancel anytime.

available on

nkoda digital sheet music subscription

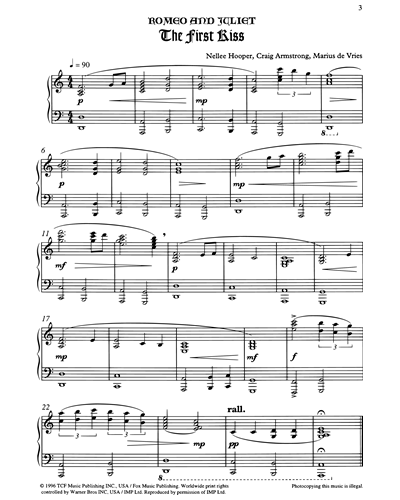

Editions

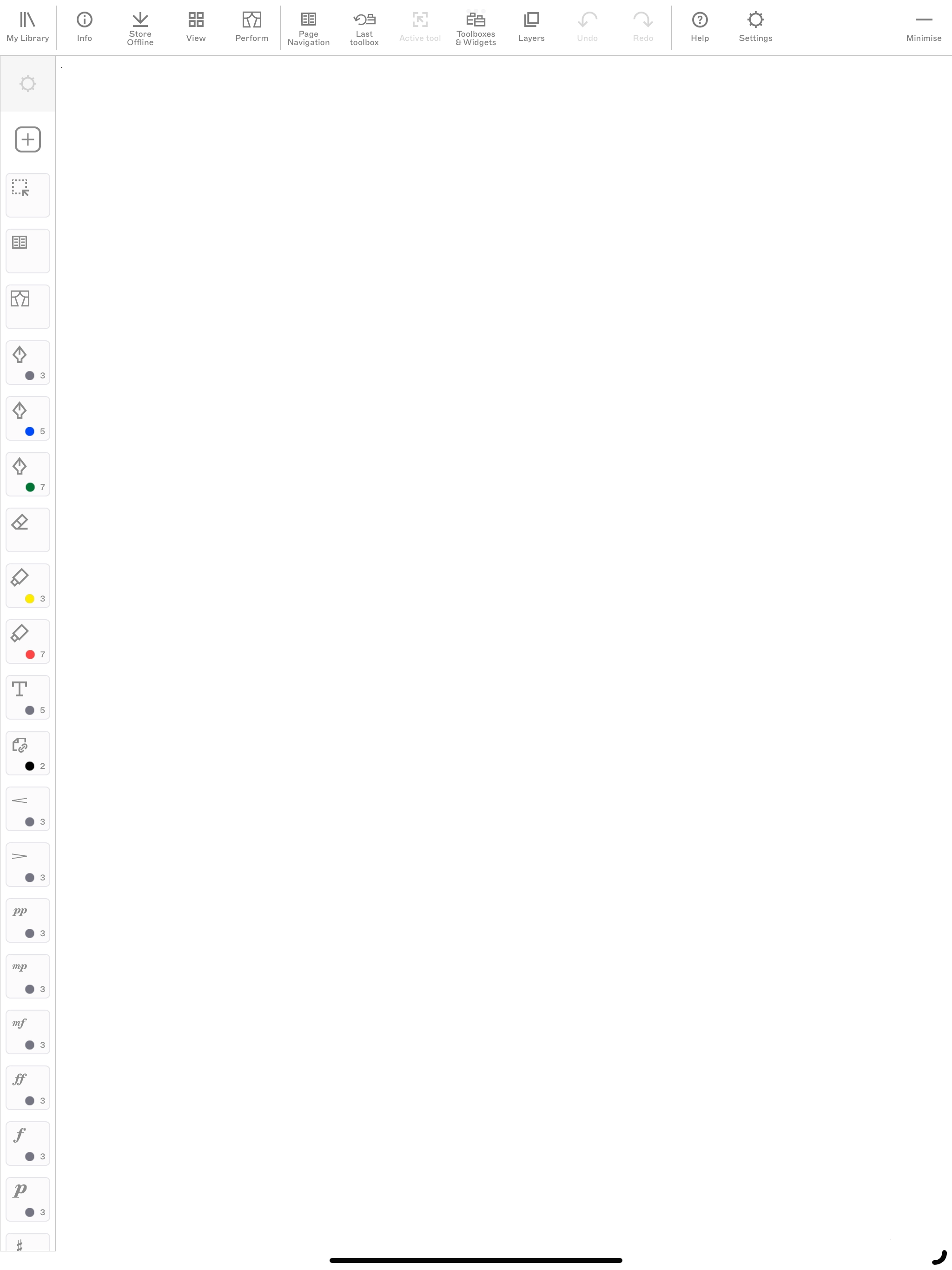

Annotate

Library

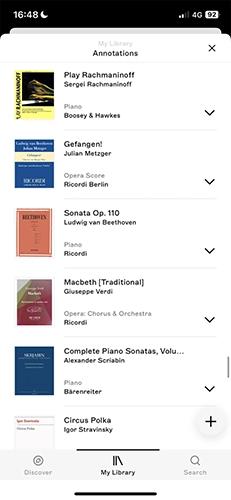

Perform

100k+ available Editions

More about Craig Armstrong

“My music is lost memories and little photographs of things that have happened,” says Craig Armstrong, summing up in a few words the melancholic, nostalgic, shifting mood of his wonderful new album, Sun on You. Across 16 tracks – just Armstrong playing piano, accompanied on strings by the Scottish Ensemble – Armstrong summons the state of mind described in the title of the final track, Saudade – a Portuguese word defined by Aubrey Bell in 1912 as meaning “a vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist, for something other than the present.” Craig Armstrong has spent the last four decades building one of the most impressive careers in British music. An early career in theatre and commercial music – working in Glasgow’s Tron Theatre with Michael Boyd and working with bands like Hipsway, Midge Ure and The Big Dish – led to work as an arranger, notably with Massive Attack and Madonna, as a solo artist, as a classical composer, and, of course, as a film composer. Armstrong’s filmography reads like a rundown of the biggest critical and commercial successes of the past 20 years or so, with Grammys, Golden Globes and BAFTAs as recognition: Snowden, The Great Gatsby, Bridget Jones’s Baby, Neds, Elizabeth: The Golden Age, Ray (for which he won a Grammy), The Magdalene Sisters, Love Actually, Moulin Rouge (for which he won a Golden Globe and a BAFTA), William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet (for which he won a BAFTA and an Ivor Novello), The Quiet American (for which he won an Ivor Novello), and scores more feature Armstrong’s music. At this point, Armstrong says, his different forms of work feed into one other. “In the early days I was conscious of making sure my classical work didn’t sound like a film score, whereas now I think it can be quite interesting when music can flow from experimentalism into tonality. I don’t see such a huge divide now. I’ve noticed that I bring quite a lot of my classical aesthetic into my film work, and vice versa. Both of these worlds are a big influence on me, and they crossbreed with one another.” What’s important, he says, is not writing something to please a particular audience, or critics, but to please oneself. That motivation was the germ of ‘Sun on You’. “Often you write something because it doesn’t already exist. You think: ‘Today I would love to hear that. With the track Saudade, there was a day in the studio where I just couldn’t find that mood on a record and I wanted to hear that, so I created it. I think that’s a big impulse for a lot of people who write: it’s not there, so just make it. I get a lot of young students coming up and asking for advice, and the best advice you can give any musician is: ‘Write what you would like to hear.’” Sun on You is Armstrong’s seventh solo recording (eighth, if you could the record he made in 2005 as The Dolls), and he views is as “an extension of the other albums I’ve made under my own name”. Still, those who know him best for the often maximalist work he has written for the films of Baz Luhrmann might be surprised by its beautiful restraint. “I think with the music I wrote for Baz, we had large ensemble pieces however there are also very tender and beautiful moments in Baz’s films which are an integral part of his film language and those pieces for me have become the most well known. What I would say is that there’s a distinction between the film work, where you’re working with lots of people, and a piano and strings album you’re doing in your front room. To me that’s the biggest contrast, rather than the musical contrast.” It’s not a uniform album, though. “I wanted to write a very melodic album however there are pieces on it like In A Remote Place that are very spacious, quite ambient and abstract. These pieces developed out of improvisation, which itself stirred thoughts and memories that fed back into the music. “Once you’ve done it you realise it reminds you of something. It’s not a conscious thing: ‘I’m going to write a piece about the day I went out in a boat and it nearly sank.’ It’s more intuitive.” Much of Sun on You was written over a couple of weeks, for Armstrong’s own pleasure. He recorded it with the Scottish Ensemble with no label in mind: “It was actually a friend of mine who listened it and said, ‘I really like that – you should put it out.’” What Armstrong does now feels wholly natural. Composers such as Mica Levi, Anna Meredith, Nico Muhly and Ólafur Arnalds work in a way that straddles genres and styles, writing film scores and classical pieces, diving in and out of pop and classical traditions as the mood takes them. It’s easy to forget it wasn’t always that way, and that Armstrong was one of the composers who paved the way for them. When he enrolled at the Royal Academy of Music in 1977 – at 17 years old, he had the terrifying prospect of Cornelius Cardew as his composition teacher – there was very definitely a right way of doing things and a wrong way of doing things in British classical music. “Stockhausen was like a god,” he recalls. “Now, if you were brave enough to write some melodies, generally speaking your professor would take you away quietly and say, ‘What the hell are you doing? Why is this not twelve-tone or musique concrète?’” He recalls one of his tutors listening to Lux Aeterna by Ligeti – for non-classical people, hardly a piece replete with hummable melodies – “and he said to me, ‘This is just like a tonal piece,’ as if he were talking about a piece by Vaughan Williams!” But Armstrong and his cohort rebelled against the straitjacket of atonal music. The same students who were writing in a serial music style were also going to see the Talking Heads, or going to Ronnie Scott’s. I loved Lol Coxhill, and I travelled to the most obscure places in London to see Lol Coxhill. So I think what’s really happened is that the dogma of that period, when you had to be one thing or another, has naturally and quite rightly broken down.” Armstrong sees music not as a series of parallel lines – pop, classical, jazz, and so on – that never meet, but as water flowing together. As the streams mingled, more people were able to discover more forms of music. And Armstrong is at the confluence of that. “It’s as if all the tributaries are flowing into the river. A lot of kids are making electronic music in their bedrooms completely democratically; then you have a lot of classically taught people going, ‘Do you know what, I’m not putting on the Boulez straitjacket’; and you had a lot of people noticing the music in movies and going, ‘We’ll go and buy that.’ These three things have come together to make a very unselfconscious way of creating music. I think history has taken us to a place where if I want to write for piano and strings, and I want to write some beautiful melodies, I’m gonna do it. So when someone says to me ‘What is this music you’ve written for piano and strings?’ it really is the culmination of lots of things I’ve been interested in my whole life, my whole career.”

Craig Armstrong sheets music on nkoda

Edition/Parts

Composer/Artist

Part

Source

The First Kiss (from 'Romeo & Juliet')

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

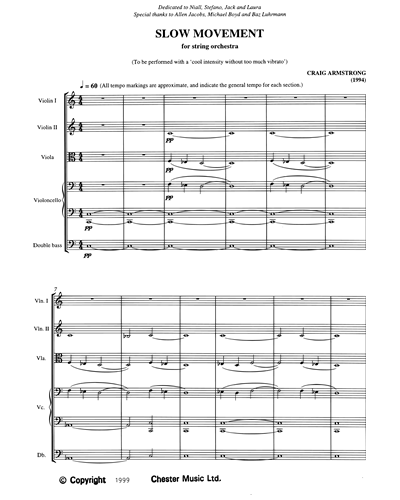

Slow Movement (from 'Romeo and Juliet')

Craig Armstrong

Strings

Chester Music

Romeo and Juliet: Balcony Scene

Craig Armstrong

Ensemble

Chester Music

Red (for 16 Voices)

Craig Armstrong

Mixed Chorus

Chester Music

In My Own Words

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

Hidden

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

Gentle Piece

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

Diffuse

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

Theme from 'Orphans'

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

Angelina

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

Childhood 2

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

Delay

Craig Armstrong

Piano

Faber Music

INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERS

PUBLISHERS PARTNERS

TESTIMONIALS