Gabriel Yared

3 pieces at nkodankoda sheet music library

over 100k editions from $14.99/month

Hassle-free. Cancel anytime.

available on

nkoda digital sheet music subscription

Editions

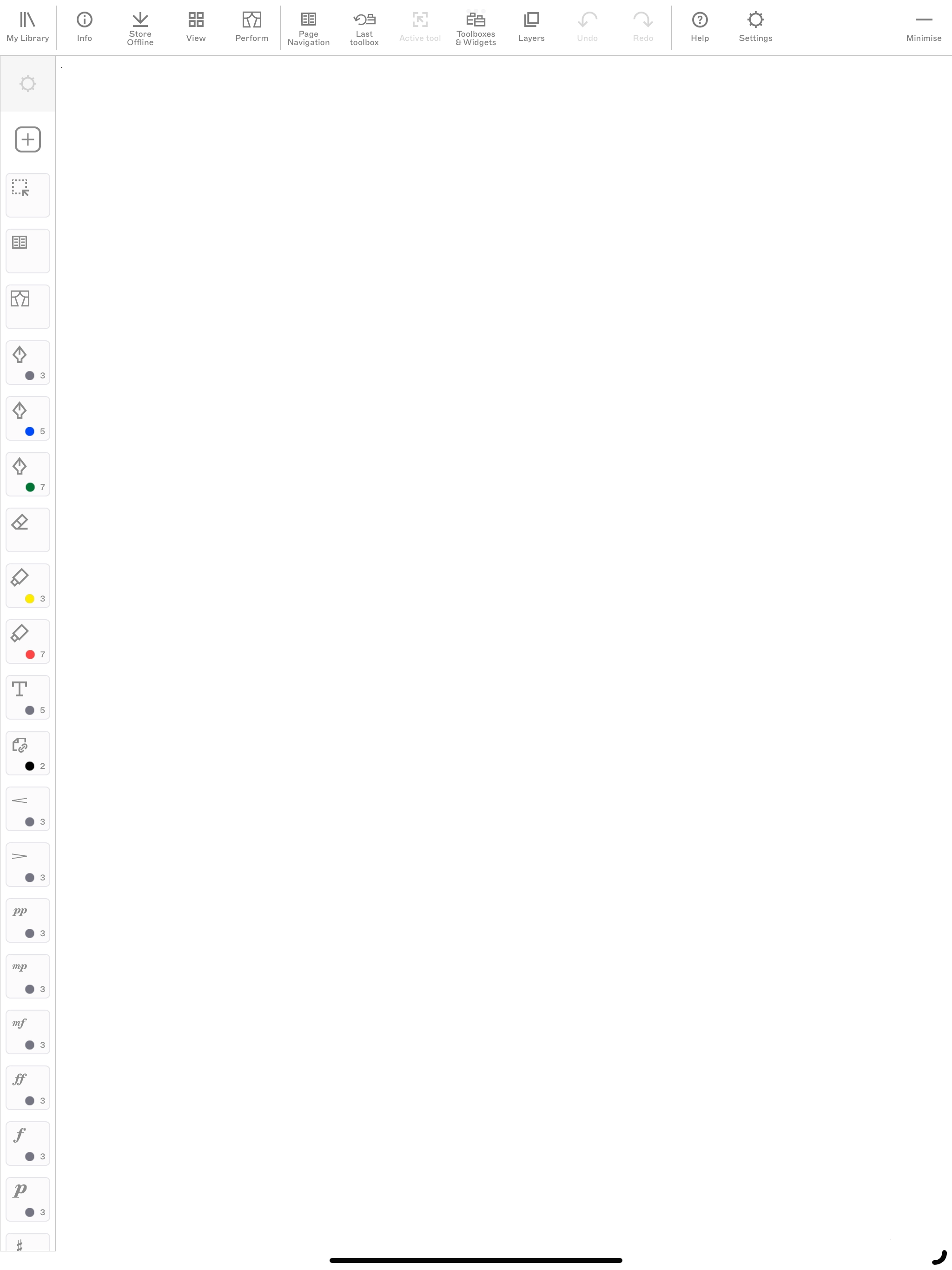

Annotate

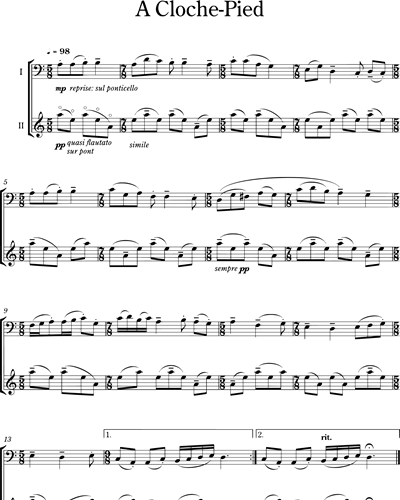

Library

Perform

100k+ available Editions

More about Gabriel Yared

"My father noticed how eager I was to touch musical instruments so he put me in the care of an accordion teacher when I was seven years old. Two years later, he stopped teaching me because he thought he had taught me all he could. At age nine, I started learning music theory and took piano lessons half an hour every week. My teacher thought that I had no future in music! Well, actually, I was not such a good pianist. I was really interested in reading music so, instead of preparing the lesson which I had been given, I would leaf through the entire book, trying to read the music. Most of my recesses were spent doing this. I understood very quickly that my path was not in performing but in composing and I already knew enough about instruments to be able to write music. I was his student until he died. I was fourteen and naturally as he was the organist of Saint Joseph University, I took his place and was able to study the organ on my own. In the Jesuits' big musical library, I read all of Bach's work for organ as well as those of Buxtehude, Pachelbel, Schumann, Liszt, Duruflé, Messiaen, Jean Langlais, Charles-Marie Widor, César Frank… This solitary work allowed me to learn writing and at age 14, I wrote a piano waltz. As my parents did not have a musical career in mind for me, I embarked on a law degree law after finishing school, where I had studied philosophy both in French and Arabic. I learnt Arabic and I have to admit that practising two languages whose writings differ - one is written from the left to the right, the other from the right to the left - helps develop a dexterity which comes in handy for writing music! So I never had a real academic music education. When I arrived in France in 1969, I was able to attend Henri Dutilleux' and Maurice Ohanna's classes as a non registered student at the Ecole Normale de Musique. Dutilleux was surprised of what I could do without having had a proper education and encouraged me to learn the rules of music composition. It wasn't until later in 1979, once I had become a fashionable light music orchestrator, that I stopped for a while to take counterpoint and fugue classes with Julien Falk, former teacher at the Conservatoire de Paris. At the end of the academic year in 1971, I went to Brazil to visit my uncle. I left for a fortnight and ended up staying a year and a half. The president of the World Federation of light music festivals, Augusto Marzagao, asked me to write a song to represent Lebanon in the Rio "Maracanazinho" Song Festival. I couldn't sing because I had lost my voice so Gwen Ovens stood in for me. She won first prize and at the Vina del Mar festival in Chile, I won third prize I almost immediately felt in harmony with Brazil. I had already written bossa nova before going there and after a month, I spoke Portuguese like a carioca. I felt at once the bliss of living the music, of making it, of learning it with great composers like Don Salvador, Ivan Lins, Jorge Bem, Edu Lobo, Ellis Regina. I felt the need to stay there and put down my roots there. I had a small orchestra of six musicians and every night, I played what I had written that day in the most well-known nightclub in Ipanema the "Number One". I gave a concert with a sax quartet led by Paulo Moura in the Cecilia Meres hall. Then I put together an album as an orchestrator for Ivan Lins. I learnt a lot in Brazil and its influence is present to this day in my work, you can see it in the Betty Blue score or in the songs I wrote for Michel Jonasz or Françoise Hardy. I appreciated in Brazil the rhythm, the harmonic acuteness, the originality of the melodic line in songs. If Lebanon is the melting pot of different cultures, Brazil is the place where you can find the perfect cultural blend between the Africans, the Portuguese and the Germans. As I applied for my "carta desanove" (Brazilian equivalent of the American Green Card), I told my friends that I was going back to Lebanon for a few days just to say goodbye to my parents before moving to Brazil for good. But I stopped off in Paris and I stayed there! Upon my arrival in France, I lived with the Costa brothers, Georges and Michel. Together, we started out in the songwriting business and for the first time, I orchestrated for strings, brass and chorus. To support my friends, I wrote it all, including the drums, the bass and the percussions. The recording studio musicians were appreciative of my work and mentioned my talent as an orchestrator to their entourage. Unfortunately, only those skills were underlined and nobody mentioned my composing work! That was the beginning of a long series of orchestrations, at the pace of two to three per day, about three thousand grand total in six years! After the collaboration Costa-Yared-Costa came to an end, I worked for Johnny Hallyday and Sylvie Vartan, Enrico Macias, Charles Aznavour, Gilbert Bécaud. From 1974 to 1980, that allowed me to write, learn, take chances, try out orchestra and rhythmic combinations. And with the money I earned, I managed to buy myself classical music sheet and keep on working. In order not to become enslaved to orchestrating, in 1976, I decided to become a songwriter as well. I worked with Françoise Hardy for whom I entirely "produced" the "Star" album : orchestration, rhythmic direction, voice direction, cover choice, song order, mixing, etc.. I went on with Michel Jonasz, Michel Fugain, Mina. I could thus get out of the orchestrating and broaden my scope to composing, artist directing and producing in general. In the meantime, I worked a lot for the advertising sector and contributed many radio and TV jingles. I was, amongst other things, in 1980 and up to now, the creator of TF1 News program jingle. I even produced an album on which I sang. I did not pursue that path but singing has always come to me naturally. When I write, I sing. Singing is to me an instinctive definition of the melodic form! Nothing prepared me to become a movie score composer. I am not a man of images, I am not a movie buff, I don't go to the movies. I am short-sighted and for that very reason, I have a hard time withstanding the omnipresence of the image on the screen! As a composer, I am a real introvert. I find the images inside me, prompted by, inspired by the words and the magic of the memory process. In spite of that, in 1975, I composed the score for "Miss O Ginie ou les hommes fleurs" directed by Belgian director Samy Pavel. But my first real experience came about with Jean-Luc Godard's "Sauve qui peut la vie" in 1979. As I worked with Françoise Hardy, Jacques Dutronc (her husband) was aware of and liked our work. He was approached by Godard for a part in the movie and he mentioned my name to him because Godard was looking for a classical musician in order to make variations on a given theme. I met with Godard. He barely talked to me about the movie but talked at length of La Gioconda, a Ponchielli opera (end of the Italian 19th century) in which four measures had caught his attention. He wanted me to find them, re-orchestrate them and create variations of them during the entire length of the movie. Just my luck, right at the time where I was fed up with orchestration ! I turned down his offer and told him instead to buy the show business guide where he could find the contact info of an orchestrator! Strangely enough, he liked our conversation, he wrote a note to me and we met again. Then again, he did not really give me the elements of the movie and I wrote the score on the basis of what he told me, without having seen a single frame of the movie. That first experience was really meaningful to me because it fitted entirely with my writing approach and in a way it justified it. The unsaid, the not yet incarnate, the yet to be filmed are amazing stimuli for the imagination process. To me, not having too many elements, not being overwhelmed by images is a very healthy attitude and a very natural one which increases the freedom of creation and imagination. From 1979 to 1983, I maintained those work principles with a certain rigidity. I only worked before and during the shooting but seldom afterwards. Later on, I became more flexible, deciding that I would work before there were any images and afterwards. I started applying that with Jean-Jacques Annaud "The Lover" and even more accurately with Anthony Minghella's "The English Patient". I have no fixed system, no specific method. Work varies, depending on the topics, depending on the individuals. But what is important to me is reading the script, my relationship with the director and step by step, with the editor, the mixer. Even though I am more flexible, I still am rigorous in my writing approach, my theme, contrapuntal, harmonic research. Similarly, when a choreographer asks me to write a score for his ballet, I read the libretto and immerse myself in the spirit of the work in order to restore a whole universe. Only later on, do the scenes get put where the choreographer wants them to be, with their approximate durations and indications on the atmosphere of the time or the dancing styles such as "brisé-haché", "brillant", hesitating waltz… The freedom to write and to imagine plays a big part here. It is then up to the choreographer to evolve with the sheet music. Of course, I would love one day to have the time to write an opera...” (Image © Peter Cobbin)

Gabriel Yared sheets music on nkoda

Edition/Parts

Composer/Artist

Part

Source

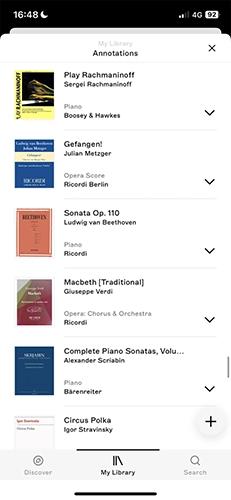

Duets for Cello

Gabriel Yared

Cello 1 & Cello 2

Chester Music

Duets for Clarinet

Gabriel Yared

Clarinet 1 & Clarinet 2

Chester Music

INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERS

PUBLISHERS PARTNERS

TESTIMONIALS